Journal

Matilda Goad's Festive Wishlist

Matilda Goad of MG&Co. reveals the cosy traditions, festive rituals, and thoughtful stocking fillers that make her family Christmas magical.

Read more

Discover the rare brilliance of chrome diopside - its vivid green hues and Siberian origins brought to life through Cassandra’s exceptional artistry.

Read more

Anya Hindmarch's Festive Wishlist

Anya Hindmarch, founder of her namesake brand, shares festive rituals and favourite stocking fillers, bringing her witty, playful design spirit to Christmas.

Read more

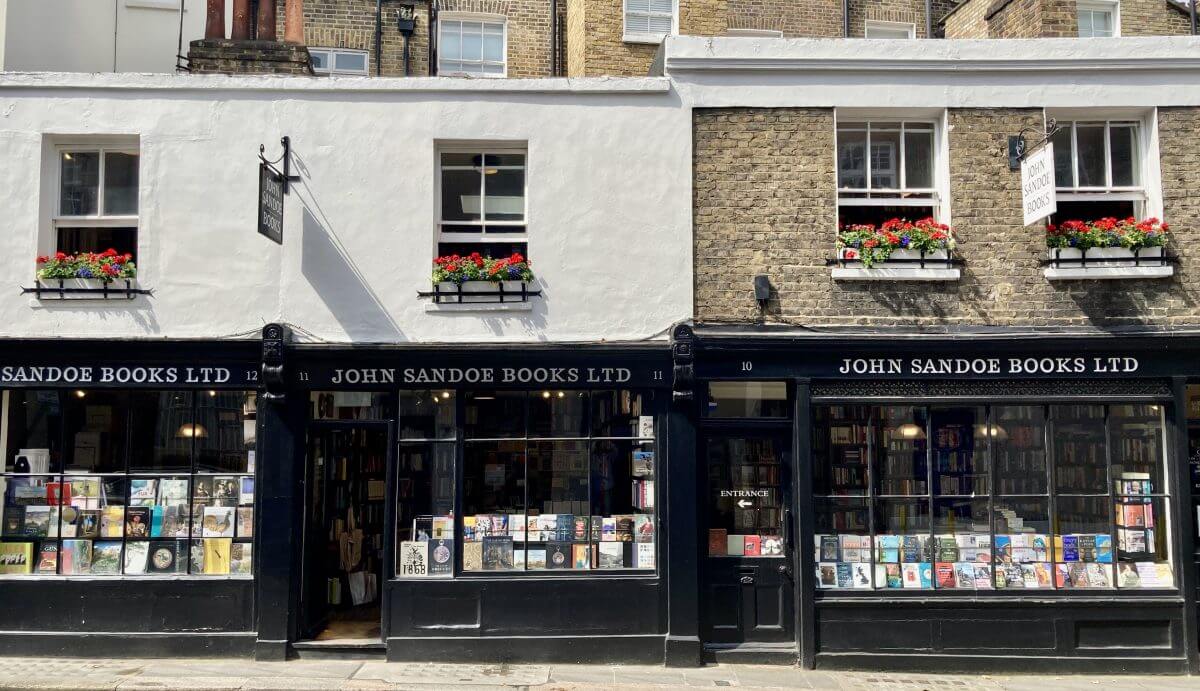

Johnny de Falbe's Festive Wishlist

Johnny de Falbe of John Sandoe Books shares his impeccably chosen small, beautiful editions - perfect inspiration for thoughtful gifts for the man who has everything!

Read more

Julian Fellowes' Festive Wishlist

Julian Fellowes, creator of Downton Abbey, reflects on Christmas, preferring fine meals and friendship over gifts, saying he no longer wishes for “more things".

Read more

Cassandra shares her festive favourites, from stocking fillers to cherished traditions, and how she combines family, luxury and giving back this Christmas.

Read more

Cassandra's Guide to London in the Winter

Explore Cassandra’s ultimate winter guide to London - from cosy spots to dine to the most magical things to see and do this festive season.

Read more